I like using composition and dependency injection, but when you need to inject each entity with multiple dependencies, it can get cumbersome fast.

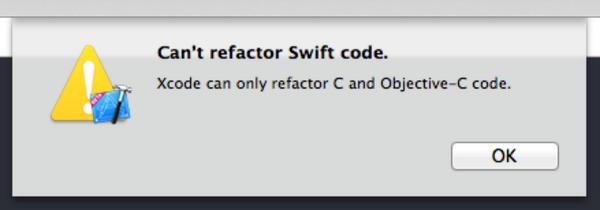

As the project grows and you need to inject more dependencies into your objects, you will end up having to refactor your methods a lot of times, as we all know Xcode doesn’t help with that.

There is a more manageable way.

Problem

Let’s say you have an object that starts needing an image provider, so you write its init something like that:

class FooViewModel {

let imageProvider: ImageProvider

init(..., imageProvider: ImageProvider)

///...

}

This is easy and convenient + it allows us to swap them it in tests.

As the application grows you will need to forward through more dependencies, each time requiring you to:

- refactor your callsites

- add new variables for them

- write same kind of boilerplate for each object

e.g. after few months this object might have 3 dependencies:

class FooViewModel {

let imageProvider: ImageProvider

let articleProvider: ArticleProvider

let persistanceProvider: PersistanceProvider

init(..., imageProvider: ImageProvider, articleProvider: ArticleProvider, persistanceProvider: PersistanceProvider) {

self.imageProvider = imageProvider

self.articleProvider = articleProvider

self.persistanceProvider = persistanceProvider

///...

}

///...

}

Since our projects contain more than one class, the same pattern will repeat many many times.

Don’t forget you also need to store references to those dependencies usually in some AppController or Flow Coordinator.

That approach leads to maintenance pain. Pain can motivate developers to take shortcuts that are far from ideal solutions e.g. using Singletons.

We want to have easy maintenance, while still getting all the benefits of direct and straightforward code injection.

Alternative

We can leverage protocol composition to make our maintenance cost lower and even increase readability.

Let’s define a generic container protocol for any dependency we have:

protocol Has{Dependency} {

var {dependency}: {Dependency} { get }

}

Swap {Dependency} with the name of your object

Swift allows us to compose protocol requirements by using & operator, that means that our entities can now contain just a single dependency storage:

class FooViewModel {

typealias Dependencies = HasImageProvider & HasArticleProvider

let dependencies: Dependencies

init(..., dependencies: Dependencies)

}

In your app controller or flow coordinator (Whatever is used to create new entities) you can store all dependencies under a single container struct:

struct AppDependency: HasImageProvider, HasArticleProvider, HasPersistanceProvider {

let imageProvider: ImageProvider

let articleProvider: ArticlesProvider

let persistanceProvider: PersistenceProvider

}

Now all app dependencies are stored in a simple data container, one that doesn’t have any logic, its not magical or anything, its just a plain struct.

This improves readability as all dependencies are stored together but more importantly it means that configuration code is always the same, regardless of what dependencies do our objects want:

class FlowCoordinator {

let dependencies: AppDependency

func configureViewController(vc: ViewController) {

vc.dependencies = dependencies

}

}

Each object defines what dependencies it uses, and those are the only ones it will receive.

e.g. a FooViewModel might require ImageProvider and our FlowCoordinator passes in it’s real AppDependency struct, Swift type handling takes care of only giving us access to ImageProvider

If down the line it needs more dependencies, e.g. a dependency of PersistanceProvider, the only thing we need to change in our code base is to tweak the typealias:

class FooViewModel {

typealias Dependencies = HasImageProvider & HasArticleProvider & HasPersistanceProvider

}

And we are done.

This approach offers following benefits:

- Dependencies are clearly defined and always consistently across any object in the project

- When object dependencies change, you only need to tweak the typealias definition

- Neither initializer nor configuration functions need to change

- Each object receiving dependencies is not getting all of them. Instead, we leverage Swift type inference and each object defines exactly what it needs